Early on the author, Paul Merry, tells us that many of his sources are already published books as well as websites. Reading between the lines, we should temper our expectations as this is not a work of research of original sources like a book by Paul Oliver or Samuel Charters. Still, Merry claims that perhaps he can put together information in a way that the reader has not yet thought about.

How the Blues Evolved is available only in digital format. It becomes quickly apparent that this is not an effort that was written by an experienced author, nor does it seem that he had the aid of a copy editor. Just in the first pages I found numerous careless errors such as author Peter C. Muir referred to as “Peter C. Muirs” or the use of “we’re” in the place where “were” should have been used. Such errors, while not disqualifying, do not inspire confidence Merry’s level of excellence.

Then there are the more substantive errors such as the assertion that “Until the description blues, for a particular style of American music, was first coined in the USA in 1912, any musical forerunner to today’s blues went under a host of other names.” Obviously, Merry is referring to the several examples of sheet music published in 1912, including Dallas Blues, Memphis Blues, and Baby Seals Blues. There are two problems with his statement. The first is that the term already existed in the sheet music of I Got the Blues, published in 1908. The second problem is that even if 1912 had been the first instance of a published blues in sheet music form, there is nothing to say that it must also be the same year that the term was coined. We need to remember that sources such as these give us only a fragmentary, and often distorted glimpse of what was happening at that time in history and that it is ill-advised to make hard assumptions based on them.

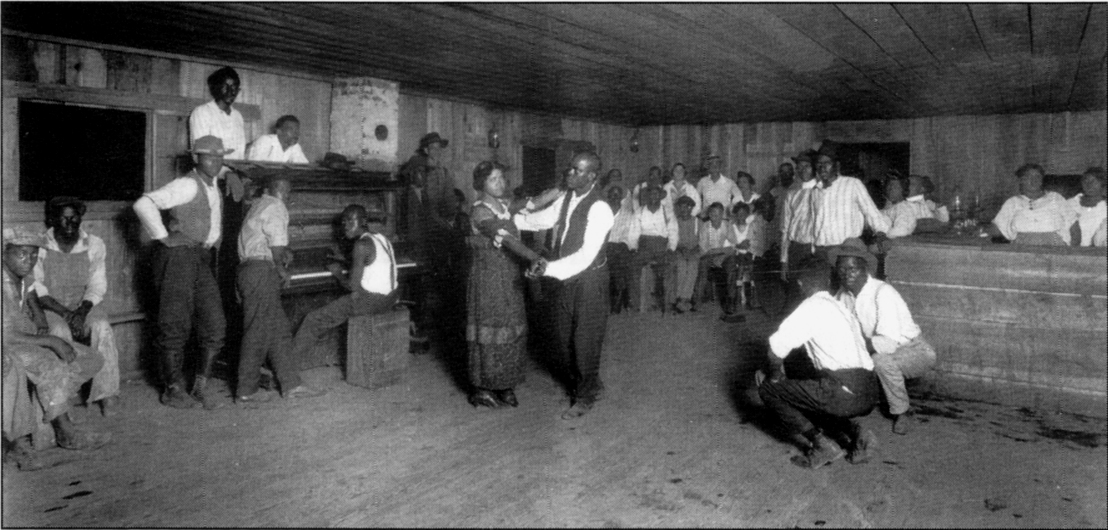

Another assertion that I find questionable is associated with the well-known picture of a barrelhouse pianist in an actual barrelhouse. Merry refers to this as a “typical” barrelhouse piano player when, since this is the only such picture known, we really have no idea how typical this particular player is. Rather, the descriptions given by a number of barrelhouse pianists indicate that barrelhouse players usually were well-dressed and stylish, not the tank-topped figure we see in this picture.

The book seems to improve a little the further it goes along, giving a logical account of the rise of minstrelsy and how it led to vaudeville and eventually the blues. However, I was harassed by a nagging feeling that the information I was reading might be inaccurate, only my lack of knowledge on the subject didn’t allow me to instantaneously fact-check it.

One passage involving Scott Joplin is especially irksome. Merry states that “Maple Leaf Rag was the first named rag published by a black artist.” The fact that this is false is hardly obscure as it is common knowledge that Tom Turpin began publishing rags two years earlier with 1897’s Harlem Rag.

In the end, this is simply a frustrating book to read. You read some passages that seem quite sound and informative only to come across a place that is so obviously wrong that it makes you wonder if Merry actually read all of the sources that he is citing. Another problem is the lack of citation notes, which this book badly needs. If you read something interesting and want to be more certain of its veracity then you could at least consult the reference cited. To sum up, the contents of the book are interesting but exceptionally unreliable.

Another note to Merry, don’t cite Wikipedia as a source. I am not a Wikipedia hater, like many out there, but its purpose has always been to summarize the many other sources that exist. Any information you find on Wikipedia should be traceable using the citations at the bottom of each page. And if there are not sufficient citations then that information should be treated as suspect.