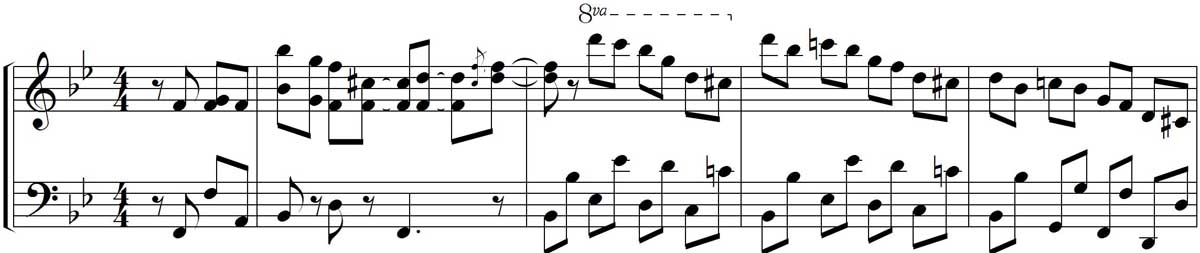

Les Copeland has been referred to as an eccentric ragtime composer and performer. In retrospect his music doesn’t seem as eccentric as it is accomplished. Like Artie Matthews, in addition to his rags Copeland published one blues, Texas Blues, in 1917. Copeland made a piano roll of Texas Blues in 1916 and that may perhaps serve as an example of his supposed eccentricity. His playing on Texas Blues is quite ragged, rhythmically, much more than would be expected even from a ragtime player. It almost seems the result of a mechanical defect in the recording mechanism, or just sloppy playing, but there is a certain intentionality evident that makes the piano roll a fascinating listen.

Copeland made one known sound recording of Texas Blues, although that was as the background music for a vaudeville routine titled Two Black Crows by Moran and Mack, made in 1927. This is not surprising since Copeland spent most of his career as a pianist for traveling minstrel and vaudeville companies. In the recording Copeland’s performance of Texas Blues can just be barely heard. Despite the poor sound quality, one significant piece of information we can glean from the recording is Copeland’s performance tempo, which is moderate and easy-going.

David Jasen and Trebor Jay Tichenor in Rags and Ragtime state that although Copeland published sheet music and made rolls in the teens, his style was that of the early days of ragtime from the late 1800s. This is a curious assessment in light of the fact that his Texas Blues was a pioneering work in being among the first to put into print a number of elements later found in barrelhouse piano recordings. Keeping in mind Jasen and Tichenor’s observation, such barrelhouse piano characteristics may in fact date back to the 1800s.

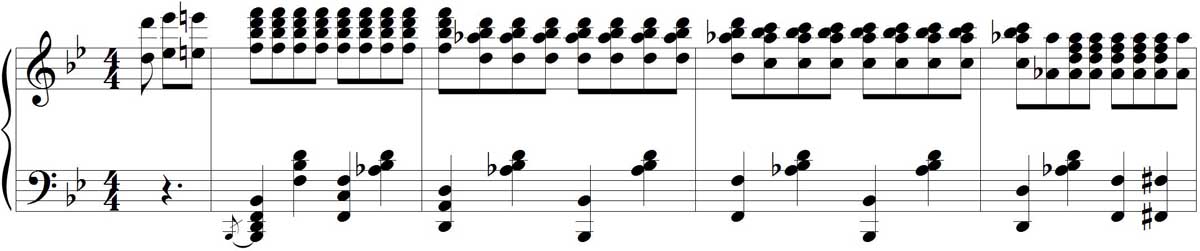

Though Copeland was from Kansas, Texas Blues is not a title of convenience but actually uses stylistic techniques known from Texas pianists. The pounded right-hand chords of Texas Blues are particularly characteristic of the barrelhouse style and would be found in later recordings, including Suitcase Blues by Hersal Thomas and Barrel House Man by Will Ezell. (Ezell is reported to have been born in Texas according to some sources. Barring that, he at least played in Texas.)

Another composer publishing during the teens, and from Texas, was Euday Bowman. His Colorado Blues has several elements in common with Texas Blues, including a descending line featuring grace-note riffs.

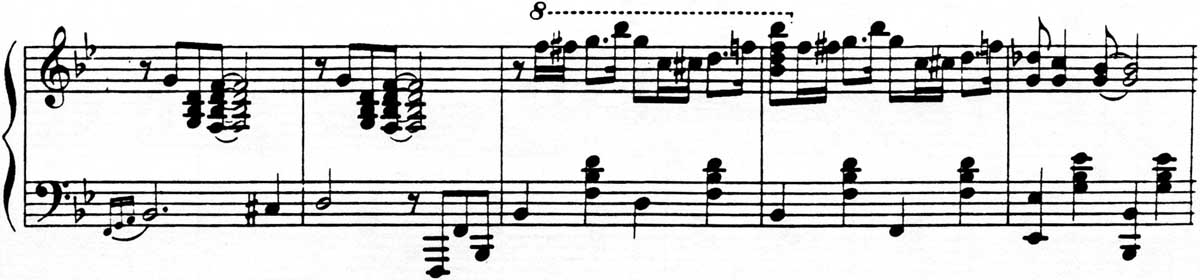

After Texas Blues, the use of similar descending lines appeared in pieces as diverse as Zez Confrey’s Kitten on the Keys and Robert Shaw’s The Ma Grinder, but Will Ezell’s Heifer Dust bears a particular resemblance to Copeland’s piano roll version as it is coupled with a nearly identical walking bass pattern in the left hand (E-flat, D, C, B-flat).

The first time this sort of descending line appeared in print dates back even further to Rags to Burn, published in 1899 by Frank McFadden, which possibly strengthens Jasen and Tichenor’s assertion that Copeland’s style was of that era.

Copeland knew Brun Campbell, also from Kansas, during that time period, according to Campbell’s recollections. Campbell also knew Frank McFadden and used his Rags to Burn version of the descending line in the later recording titled Chestnut Street in the 90s, Campbell’s commemoration of the ragtime music from that era.

An additional detail that indicates that all of these pieces may be related is that Texas Blues, Colorado Blues, Rags to Burn, Chestnut Street in the 90s, and Heifer Dust are all the key of B flat, not an especially common key for blues. Perhaps that suggests that what we are seeing is a continuous development of the same piece of music, passed on from one composer to another.

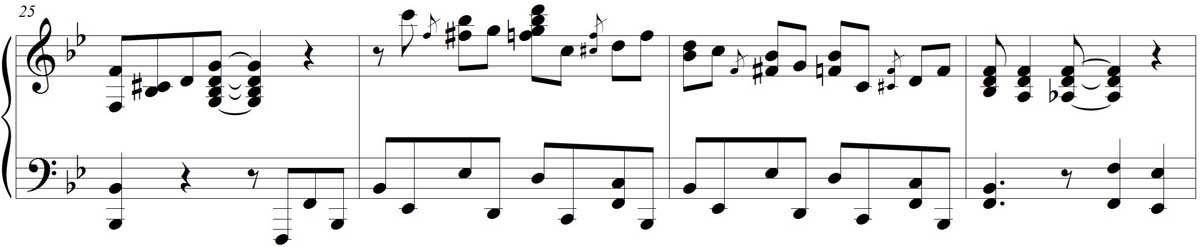

Another groundbreaking element in Texas Blues is the use of a repeated blues riff which had not really occurred in publications before, although it is possible to make the case that Antonio Maggio’s I Got the Blues from 1908 features a prototypical version of this riff.

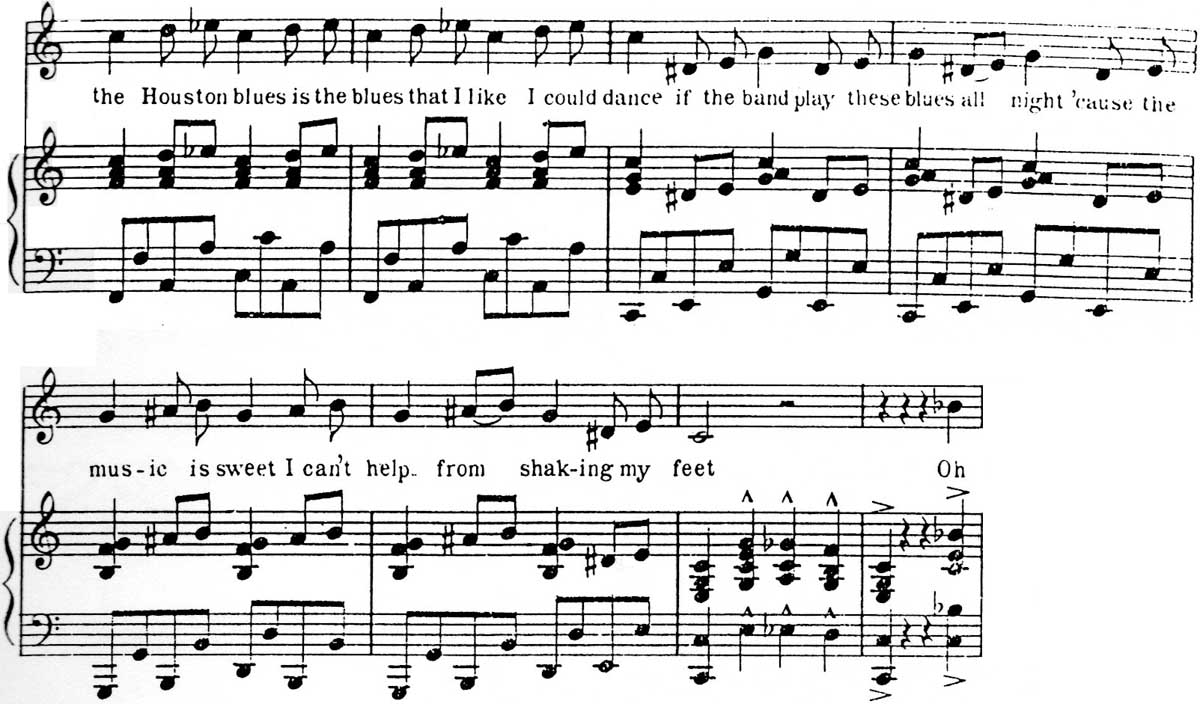

The same riff showed up a year after Texas Blues was published in George W. Thomas’s Houston Blues, before he relocated to Chicago. This suggests that the idea of the riff, and the particular riff itself, was already present in Texas.

George W. Thomas continued to use this riff in his compositions extensively, including Shorty George Blues and The Fives.

Unfortunately neither Les Copeland’s scores nor his piano rolls have been gathered together as collections. The score for Texas Blues can be found in the compilation Gems of Texas Ragtime. It is now out of print but copies do surface from time to time on Amazon and eBay.