George W. Thomas was one of the most pivotal figures in the development of piano blues. His New Orleans Hop Scop Blues is one of the earliest blues known. Even more significant is that Thomas is known to have originated three bass patterns used in boogie woogie: the walking bass, standing bass, and the arched pattern first published in The Rocks.

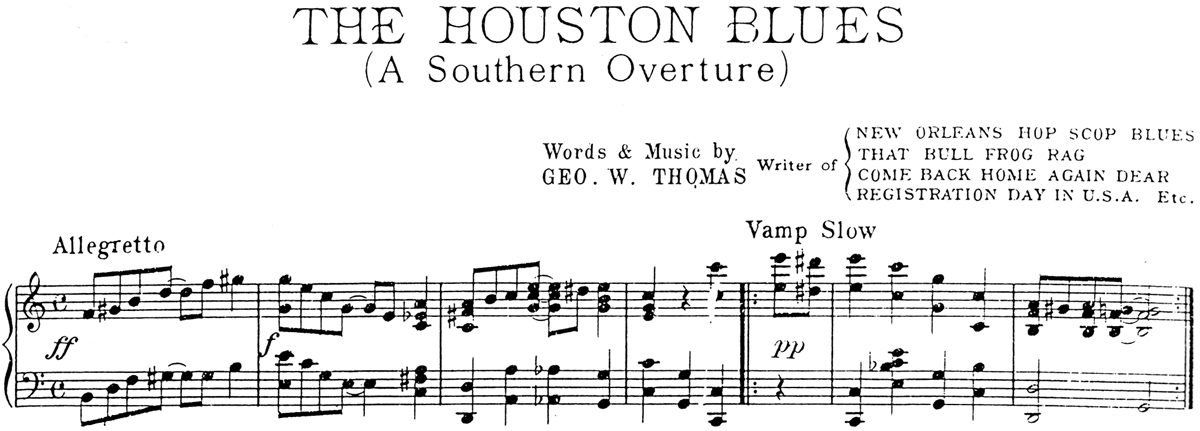

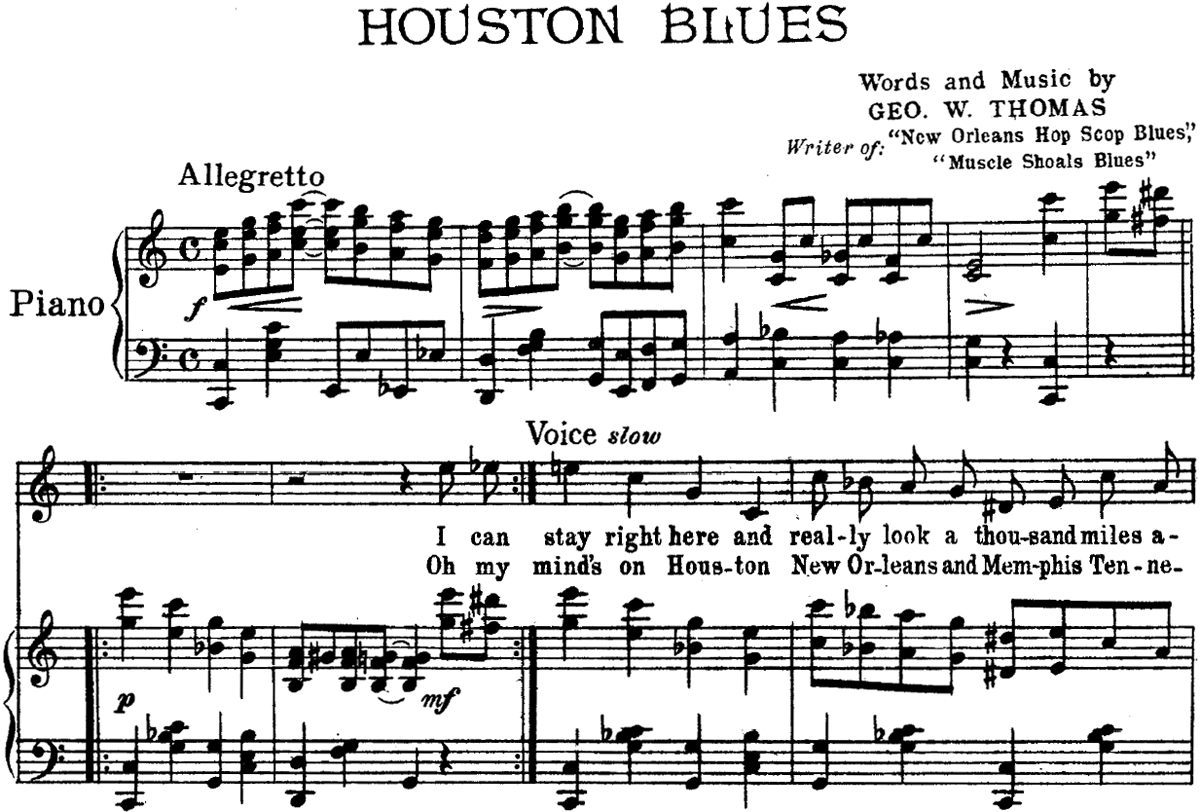

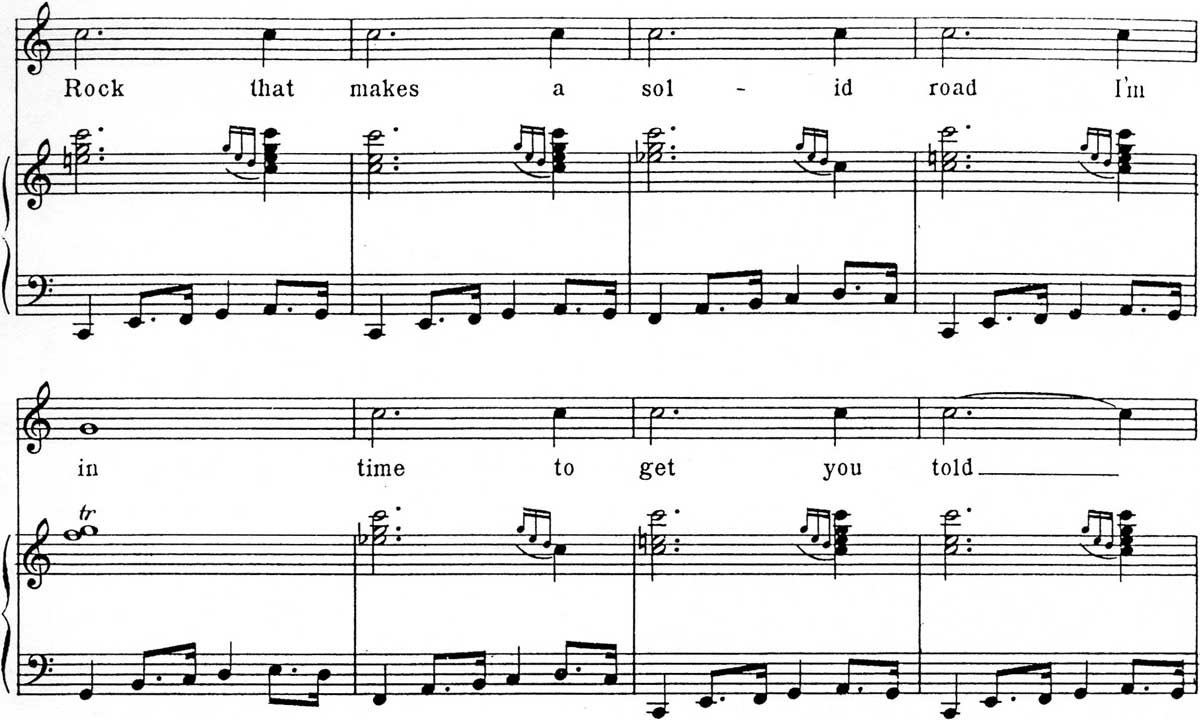

Thomas started out very close to the ragtime tradition, reflected by compositions like That Bull Frog Rag and That Rat Proof Rag. New Orleans Hop Scop Blues, published 1916, and Houston blues, published 1918, also contain ragtime elements such as diminished-seventh chord introductions. After Thomas had acclimated to the Chicago blues scene, Houston Blues was republished in 1922 with a more contemporary introduction.

Another difference was that the 1918 version of Houston Blues changed key between the verse and chorus while the 1922 version kept both sections in the same key, more typical of the blues.

Caldonia Blues, although not a typical example of Thomas’s writing, is in some ways a perfect representation of who he was relative to his surroundings during the 1920s. It is a curious mix of South Side Chicago and country blues elements, which Thomas brought with him from the south. One aspect connecting it with country blues is that the entire piece consists of variations on a single theme. Stylistically, the piano roll of Caldonia Blues could have been a Jimmy Blythe performance were it not for the harmonic progressions. More typical of Thomas, Caldonia Blues uses an extended blues progression with an unusual emphasis on the tonic harmony, reminiscent of certain country blues guitar players who played some songs with a constant tonic drone.

Here is the modified blues progression in measures 2-16, each numeral representing a bar. The first stanza has an extra two bars added for a total length of 14 bars:

I IV I I I I – I I I I – V V I I

Another connection to country blues is the chromatically-descending figure in the right hand. Similar features are found in songs like Bo Jones’s Leavenworth Prison Blues.

The harmonies in Caldonia Blues are clearly much more basic and less jazz-based than in Jimmy Blythe’s piano rolls. But a little of Blythe’s influence shows up at the end when the Caldonia Blues ends on an inconclusive FMm7, a IV flat-7. This is similar to Blythe’s sound recording of Chicago Stomp which also ends on a IV flat-7.

Thomas’s development of boogie woogie began with The New Orleans Hop Scop Blues, which contains an early broken-octave walking bass figure. While published in 1916, the Hop Scop Blues was reported by Clarence Williams to have been performed by Thomas in 1911, making it the first known composition with a walking bass. That is not to say that it is the first piece ever to use the walking bass, just the first that we are aware of. The first publication has the walking bass notated with grace notes but later editions use the standard eighth notes instead.

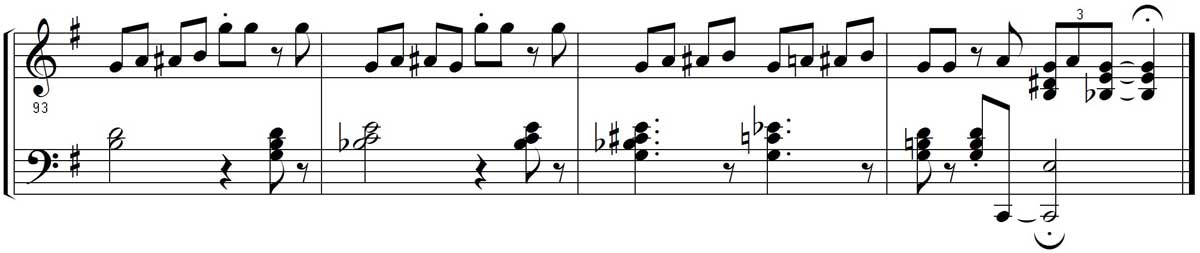

George W. Thomas was an eclectic composer and would even switch styles in the middle of a composition. In the 1923 record of The Rocks, for example, in the introduction we hear some almost classical-sounding arpeggios, followed by a blues progression, more classical arpeggios, a rustic-sounding section, another quasi-classical section with counterpoint between the right and left hands, and a reprise of the rustic section. The middle section with counterpoint also features a boogie woogie-style walking bass.

The Rocks is commonly credited as the first sound recording with a boogie woogie style walking bass, sometimes clarified as the first walking bass in a 12-bar blues. Even with that caveat, the assertion is not quite accurate, for a couple of reasons. First is that the walking bass section is not a 12-bar blues. Only the first section of The Rocks bears any similarity to the blues. Second, the portion with the walking bass is not really part of The Rocks but was interpolated by Thomas from an earlier publication of his, That Rat Proof Rag from 1917.

However, this reminds us that George W. Thomas was using a walking bass years before boogie woogie began, even as part of his ragtime oeuvre. In any case, Thomas’s place in the history of the development of the boogie woogie style is certain, as the following examples show.

In the section of The Rocks with the blues progression Thomas is the first to use this arching bass pattern:

This bass would be used in many future blues and boogie woogie pieces, including The Wicked Fives by Lemuel Fowler, No Special Rider by ‘Little Brother’ Montgomery, and several recordings by Albert Ammons including Boogie Woogie Blues, Monday Struggle, and Shout for Joy.

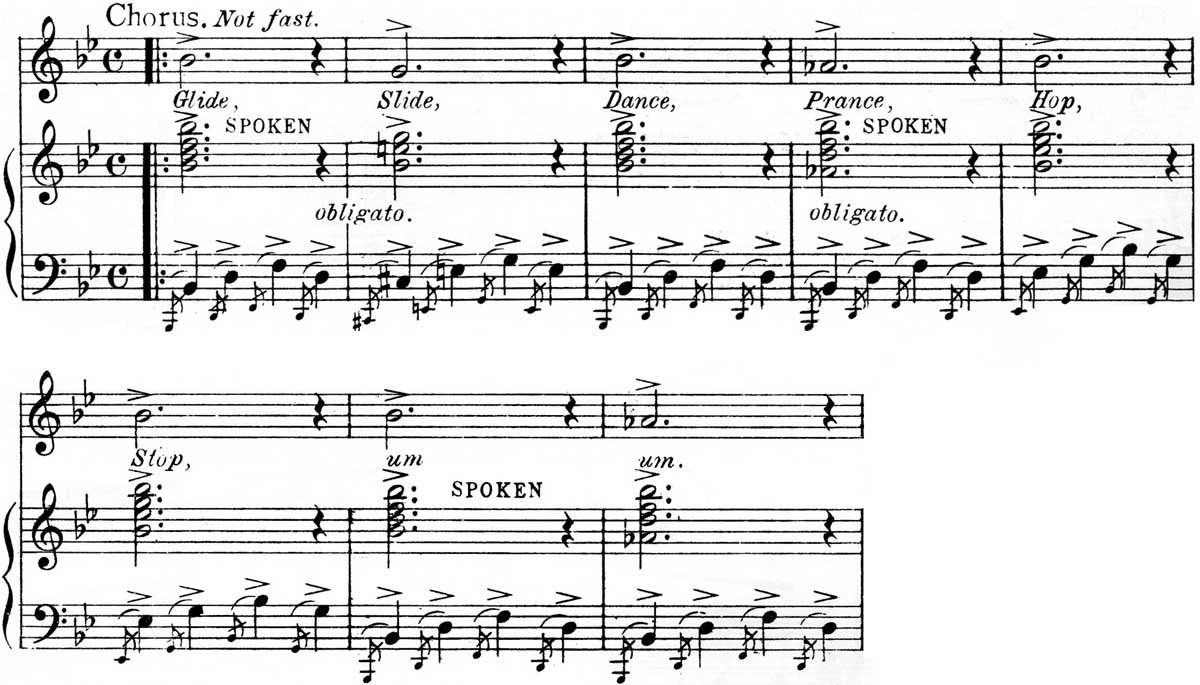

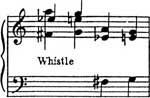

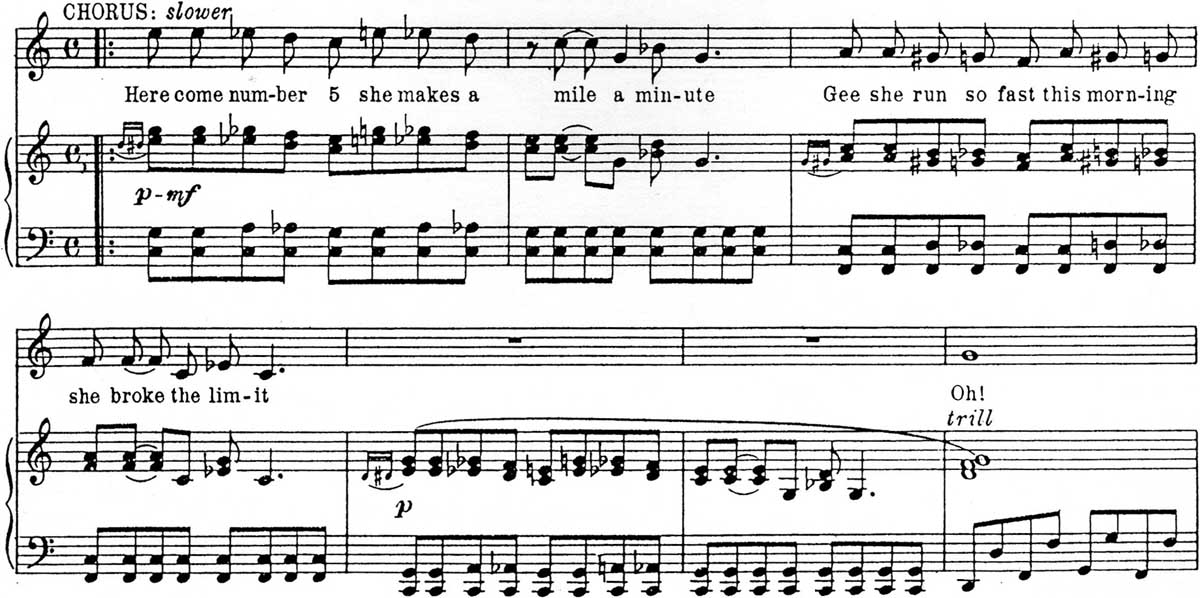

Written by George W. Thomas along with his brother Hersal Thomas, The Fives was published in sheet music form as a song with piano accompaniment in 1922. The Fives sounds a little more like boogie woogie than The Rocks and was recorded later by Clarence Lofton in a true boogie woogie style. What is also apparent is that this piece has a train connection. We can tell that from the cover of the sheet music, the lyrics of the song, and from a place in the score that indicates a whistle. There is still another train connection because on the first page The Fives quotes from Ole Miss Rag, published by W.C. Handy eight years earlier, which is also train-related. We can also see a similarity in the sheet music covers. The Fives is significant historically because it is the first time we see a “standing bass”. In a standing bass there is a stationary note on the bottom while one or more notes move above it.

Clarence Lofton in a true boogie woogie style. What is also apparent is that this piece has a train connection. We can tell that from the cover of the sheet music, the lyrics of the song, and from a place in the score that indicates a whistle. There is still another train connection because on the first page The Fives quotes from Ole Miss Rag, published by W.C. Handy eight years earlier, which is also train-related. We can also see a similarity in the sheet music covers. The Fives is significant historically because it is the first time we see a “standing bass”. In a standing bass there is a stationary note on the bottom while one or more notes move above it.

The standing bass was new in the 1920s but by now it is quite familiar to us, and we also recognize its connection with train sounds. Anyone old enough to remember Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood may recall a theme that went along with the trolley, not too different from the standing bass for The Fives.

This intuitively sounds like train music to us today, but that all started with George W. Thomas. The Fives is one of those historically-curious pieces of music that sows the seeds of the future, but also has connections with the past. Unlike mature boogie woogie, it still has a sectional structure with verse and chorus (and a middle section in the piano roll). And for much of the verse it still uses the ragtime marching bass.

George W. Thomas is considered a primary developer of boogie woogie and the closest he ever got to that style may be Shorty George Blues. Although the sheet music was published in 1924, George Thomas and vocalist Tiny Franklin made a recording of Shorty George Blues in December of 1923. This recording of Shorty George Blues can be found on the Document Records CD, Piano Blues Vol. 4, along with three other recordings from the same session by Thomas and Franklin. In the liner notes of the CD, Julian Yarrow states that this session is “the earliest sustained presentation of the boogie woogie form on record.”

Shorty George Blues might indeed be considered the first published piece in boogie woogie style and perhaps even the first boogie woogie recording. This is supported by the fact that Shorty George Blues is the first George W. Thomas piece to have only repeated choruses, instead of the verse-chorus structure, as well as a consistent walking bass like mature boogie woogie. Two potential problems are the fact that the recording is not a piano solo and the tempo is comparatively slow. As for the first issue, we must consider that two of Thomas’s other compositions, The Rocks and The Fives, were published as vocal songs yet were recorded as piano solos and became early boogie woogie standards. Additionally, if you consider Roll ‘Em Pete a boogie woogie recording, performed by Pete Johnson with vocals by Big Joe Turner, then it is hard to disqualify Shorty George Blues. As for the speed, it does not take a great acceleration in tempo before Shorty George Blues starts sounding like Jimmy Blythe’s Chicago Stomp, recorded in 1924, which is considered by many to be the first boogie woogie piano solo recording. Certainly Chicago Stomp is more in the nature of classic boogie woogie, but Shorty George Blues bridges an important gap between songs that merely utilized a walking bass in sections and later ones that used the walking bass throughout.

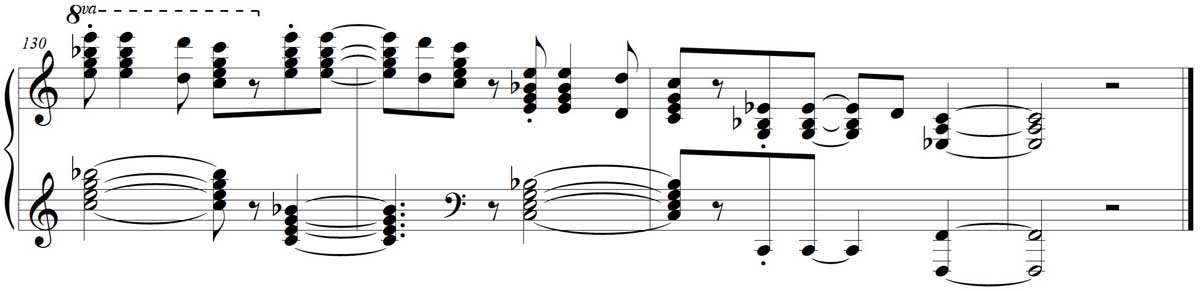

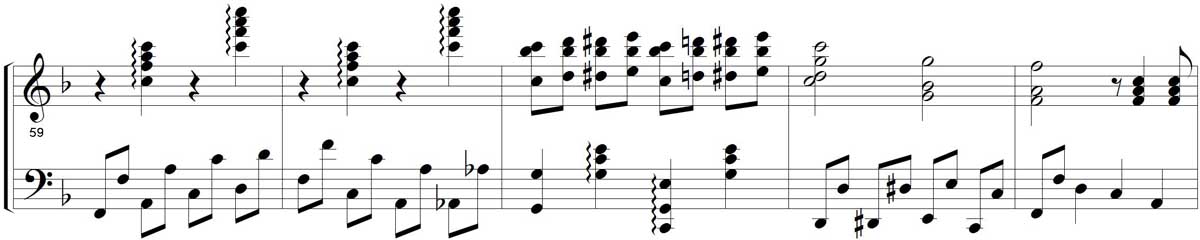

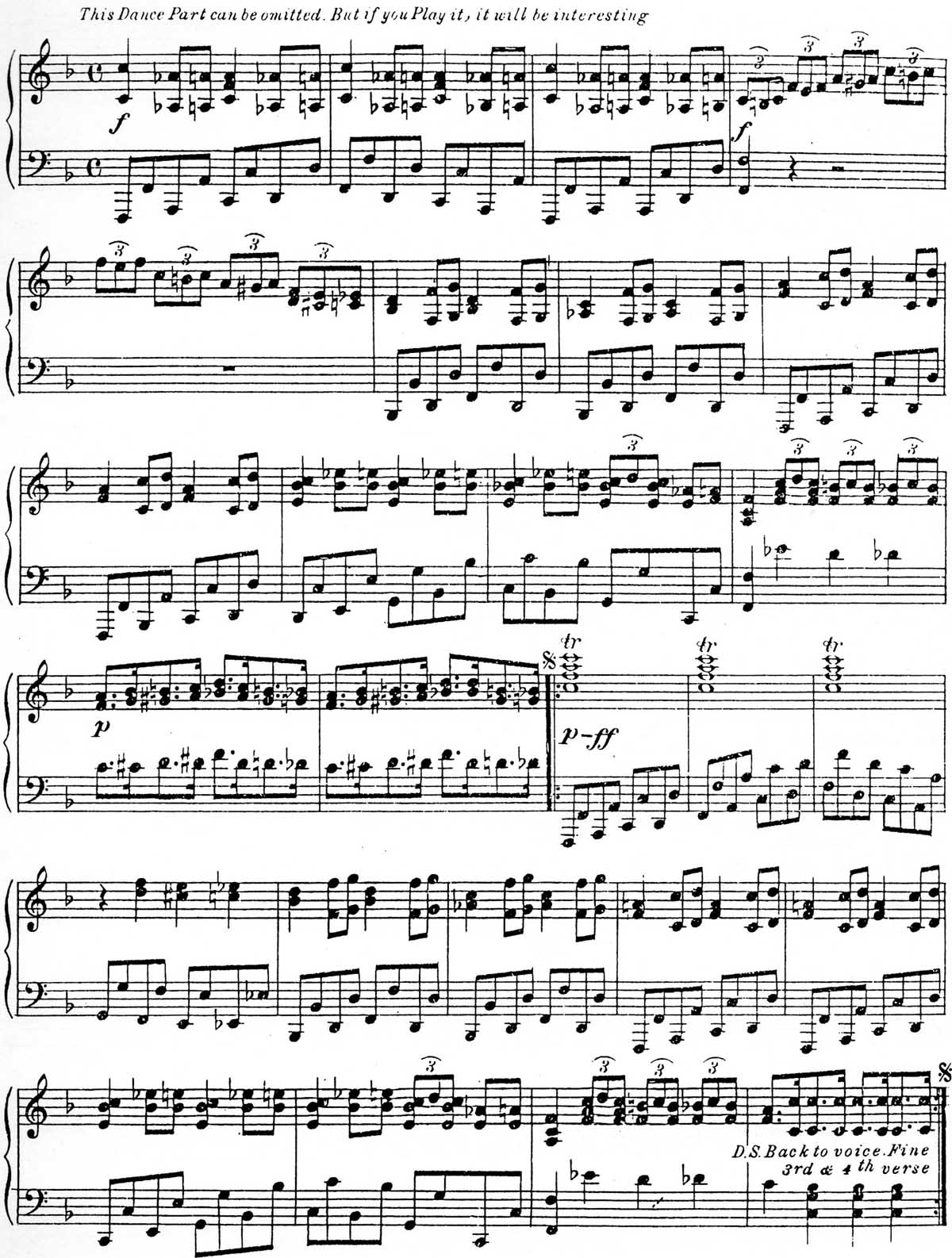

Included in the score of Shorty George Blues but not in Thomas’s recording is a “dance” section where the piano takes on a solo role for two choruses. It may be possible to consider the dance section alone as the first boogie woogie piano solo. In that section we see some elements that became common in boogie woogie such as a right hand tremolo, foreshadowing Chicago Stomp, and a break, foreshadowing the breaks in Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie. The entire dance section is reproduced here:

In the score Thomas indicates “This dance part can be omitted. But if you play it, it will be interesting.” It seems odd, then, that Thomas did not perform the dance section on the recording. Since the recording was made the year before the sheet music was published perhaps that section had not yet been composed yet.

Although Shorty George Blues was not cited as a standard by Albert Ammons the way that The Rocks and The Fives were, it is actually closer to the eventual boogie woogie style and did have some influence on later recordings. The closest resemblance is Will Ezell’s Playing the Dozen which at times sounds like a direct copy.

George W. Thomas’s sound recordings can be found on Texas Piano 1 from Document Records. Thomas accompanies Tiny Franklin in four of his compositions on Piano Blues Vol. 4 from Document Records. A recording of the piano roll for The Fives, incorrectly attributed to Hersal Thomas, can be found on Boogie Woogie Blues from the Biograph label.

Sheet music for The New Orleans Hop Scop Blues is included in the collection, Beale Street and other Classic Blues, compiled by David Jasen.

Sheet music for The Rocks, The Fives, and Shorty George Blues are included in Richard Riley’s Early Blues Folio #2, available on his website Pianomania.com. You can order the folios directly from him using the contact information on the site.