Robert Shaw was one of many barrelhouse pianists to never record during the classic blues era. We are highly fortunate that he was given the opportunity later on during the 1960s blues revival because Shaw gave us a perfect snapshot of Texas barrelhouse music from that earlier era, and with higher fidelity recordings.

A big part of the sound of Texas barrelhouse, and the Houston-based ‘Santa Fe’ group in particular, is the apparent rhythmic complexity. One effect achieved in The Ma Grinder is a rhythmic interplay between the right and left hands that is not typical for most piano blues in that the two hands sometimes take turns playing on the beat. In the first measures of The Ma Grinder the left hand plays on beats 1 and 4 while beats 2 and 3 are supplied by the right hand. The result is a wild, unsettled rhythmic feel that is not usually found in the blues and seems to owe something to ragtime.

Lavada Durst (aka Dr. Hepcat) stated “I met Robert Shaw around 1933. Robert was a master of barrelhouse blues. He played that Sugarland style of fast piano, which combined blues with ragtime and stride.” Nevertheless, The Ma Grinder with its left-hand syncopations departs from the usual arrangement found both in ragtime and blues piano which has a steady accompaniment in the left hand with syncopations in the right hand. The result is that Santa Fe is one of the most distinctive and individual of all the blues styles.

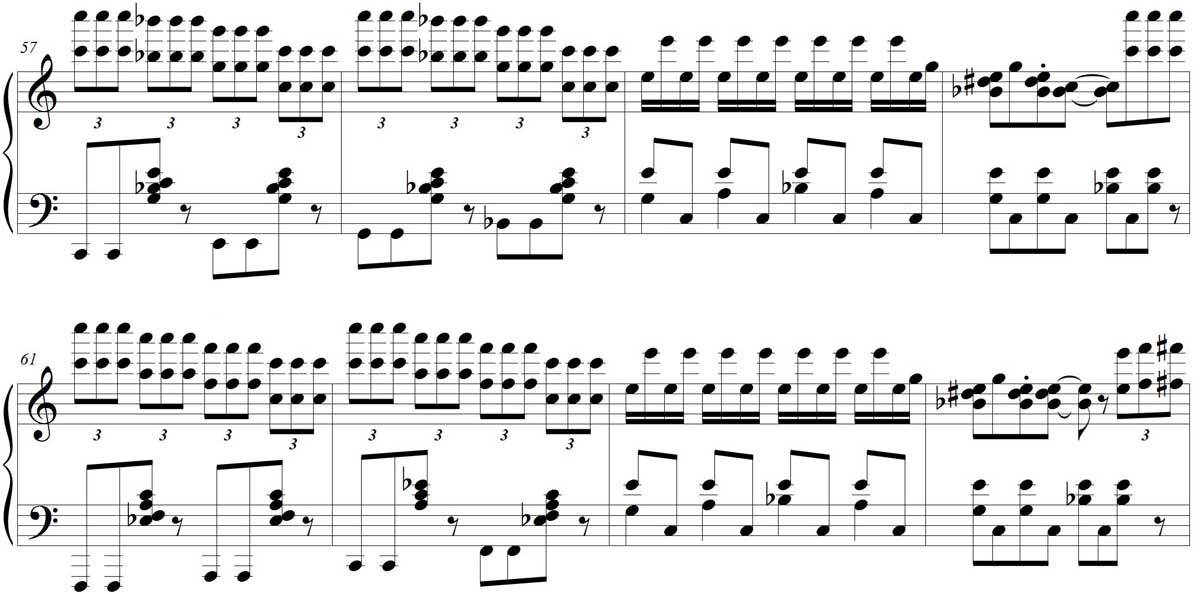

According to Mack McCormick, Shaw learned an unusual playing technique from a man with a withered left hand who had to play bass notes with the edge of his hand. Shaw used this technique in several pieces, including the following passage in The Ma Grinder:

Curiously, similar passages can be found in Chicago in the 1920s, in pieces like Jimmy Blythe’s piano roll of When Grandpa Steps Out.

Since, according to Shaw, the Santa Fe tradition goes back to around 1920, it may be possible that George W. Thomas, originally from Houston, took this musical idea with him when he relocated to Chicago. Indeed, a slower variant can be found in Thomas’s piano roll of Dead Drunk Blues.

The descending and ascending chromatic figure featured in The Cows (m. 17-18) is another element from Texas tradition as it is found also in Conish Burks’s Mountain Jack Blues, Black Boy Shine’s Brown House Blues, and Cows See That Train Comin’ by Joe Pullum and Rob Cooper.

Lyrically, the label of “The Cows” is related to Pullum and Cooper’s Cows See That Train Comin’ and Burks’s Mountain Jack Blues. Mountain Jack Blues draws a parallel between cows and trains by comparing cattle lowing to the “holler” of a train whistle. Cows See that Train Comin’ has references to trains but only mentions cows in the title. However, as in Mountain Jack, “cow” is clearly a reference to a woman.

In another similarity with Jimmy Blythe that seems too suspicious to be coincidental, a chromatic line voiced in exactly the same register (alto) appears in his Society Blues. The only difference is that Blythe’s chromatic line is descending only. This gives us a clue that there may be more connection between the Chicago and Santa Fe styles than we might have thought.

Robert Shaw’s best recordings were made in 1963 and released on the LP, Texas Barrelhouse Piano. Those recordings have been included on the Arhoolie CD, The Ma Grinder, along with some additional recordings made in 1976. Robert Shaw 1971 Party Tape is an interesting artifact of Shaw in a relaxed live setting. Just a little louder than the background noise, he goes through most of his standard pieces and bits of others. It’s also interesting to hear Shaw’s interpretations of Pine Top Smith’s Jump Steady Blues and Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie. Some other Shaw recordings are on Giants of Texas Country Blues Piano although there is little there that isn’t also on his original album.