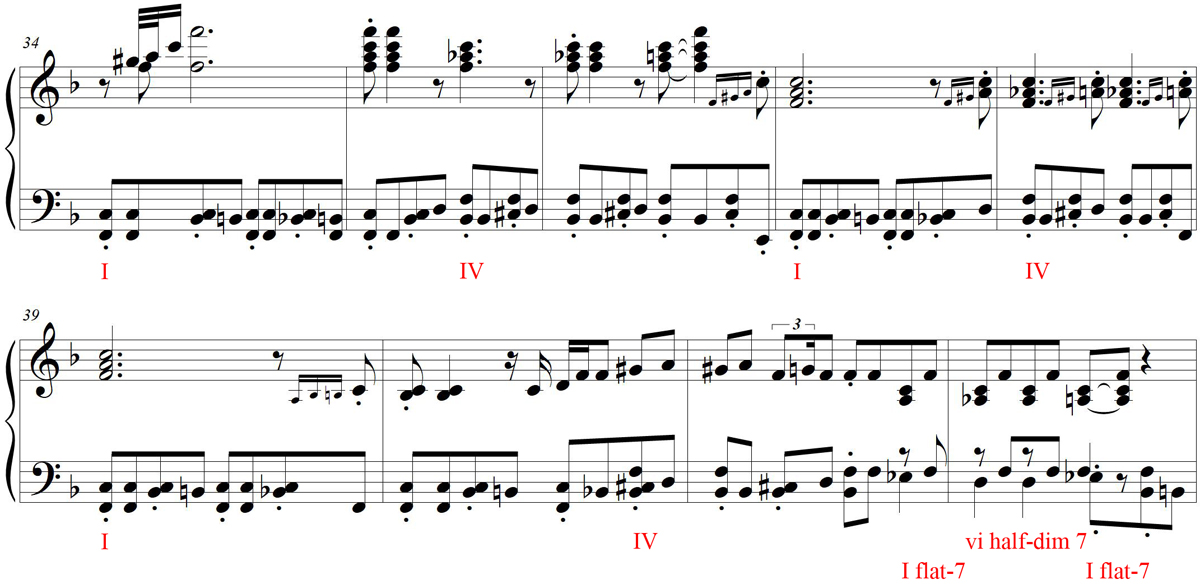

Wesley Wallace is one of the more mysterious figures in St. Louis barrelhouse piano history. All of his known recordings use only the I and IV chords of the usual blues progression, leaving out the V chord. Wallace’s phrases are also widely variable in length, with Fanny Lee Blues ranging from 6 to 11 bars per chorus, sometimes including half bars. Here is a characteristically idiosyncratic progression from Fanny Lee Blues:

Wallace accomplishes a cadence at the end of the phrase by using a neighbor motion between E-flat and D, and A and A-flat. These half steps down from E-flat and A create double leading tones that give the impression of a resolution to the tonic. It is possible to see this as an alternation between I flat-7 and vi half-diminished 7, keeping in mind how Buck McFarland used a vi chord to replace V in On Your Way and similar pieces.

These structural and harmonic peculiarities make Wallace’s playing distinctive but resulted in some difficulty when he accompanied singers. In the case of Dying Baby Blues, it appears that the singer, Robert Peeples, is caused some discomfort when the expected V chord does not appear at the end of the phrase.

While some might consider these irregularities as defects in Wallace’s playing, his two piano solos, Fanny Lee Blues and Number 29, are creative and engaging in their own way.

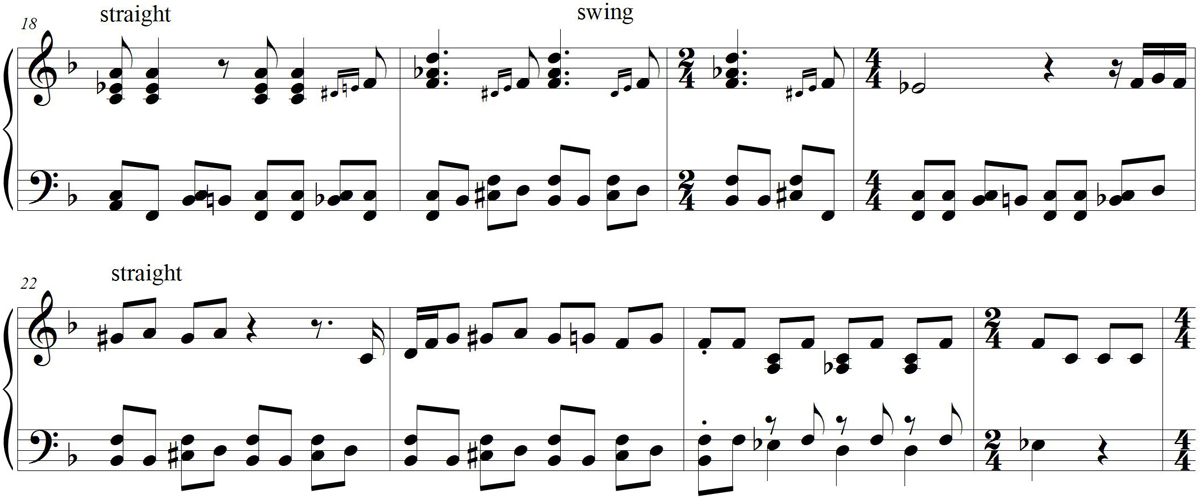

An individual aspect of Fanny Lee Blues is the way the rhythm vacillates between swung and straight at various places in the recording. The use of swung versus straight rhythm varies widely among blues players. Sometimes the same artist will play with a straight rhythm in one piece (e.g. Doug Suggs’s Smoke Like Lightning) and swung in another (e.g. Doug’s Jump). But in the case of Wallace’s Fanny Lee Blues, the amount of swing can change even from one bar to the next.

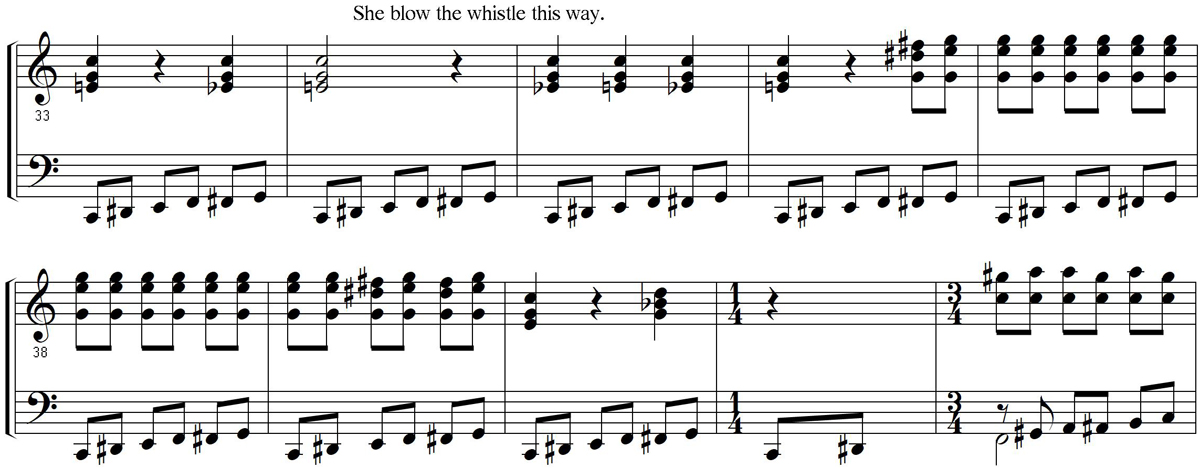

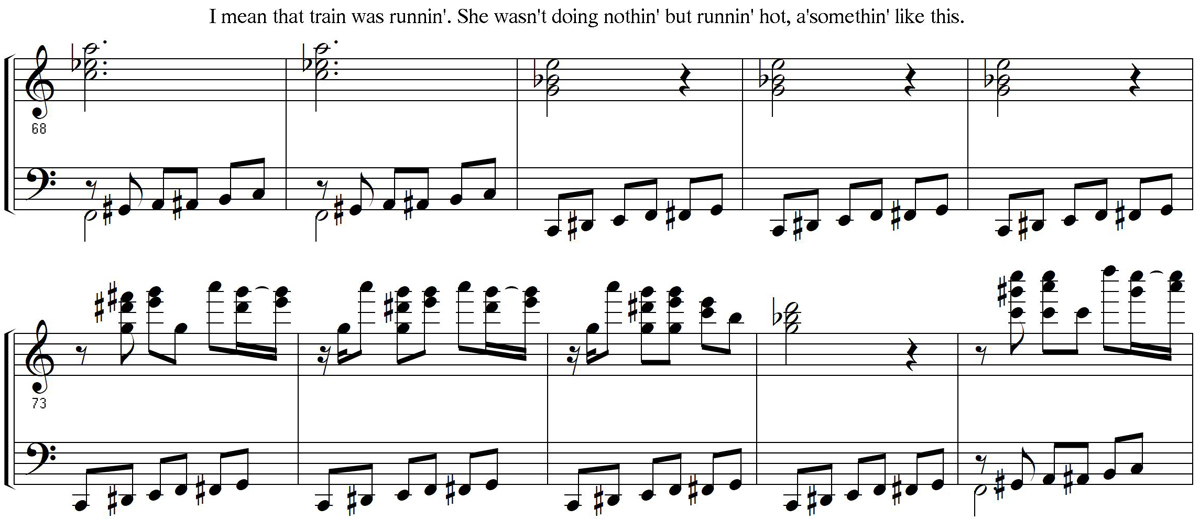

Number 29 is in an unusual 3/4 meter with a restless, running 8th-note chromatic figure depicting the motion of a train. Wallace frequently drops beats, with resulting 1/4 and 2/4 measures scattered throughout.

Over top of this perpetual motion backdrop are various imitations of train noises such as the whistle blowing and the engine running hot.

These examples of a musical parallel to onomatopoeia serve the spoken story of Wallace catching a train from Cairo, Illinois to East St. Louis. Number 29 and Buster Pickens’s Santa Fe Train are two of the most interesting documents that we have of the train-hopping travels of the itinerant barrelhouse pianists from this time.

Below is a transcription of the words spoken during Number 29, as best as I could decipher them:

This train a’called twenty-nine.

Leavin’ outta Cairo, comin’ East St. Louis.

‘Fore she got to Murphysboro, she blow that a’whistle.

She blow the whistle this way.

I caught that train in Murphysboro,

I was intendin’ to get off at Sparta, Illinois.

I mean that train was runnin’.

She wasn’t doing nothin’ but runnin’ hot, a’somethin’ like this.

Just ‘fore she got to Sparta, she thought she blow that a’whistle again,

She blow that whistle somethin’ like this.

She’s lopin’ now. (The intended word appears to be “loping”, as in galloping.)

I want to get off that train, but she’s goin’ too fast.

I haul away and touch one foot on the ground; my heel like knock my brains out.

I haul away and shut both eyes right tight, and fell off.

This is the noise I made when I hit that ground.

I’m rollin’ now.

I got up and waved my hand, told her goodbye.

This way she just keep walkin’ on in to East St. Louis.

There has been controversy regarding the identity of Wesley Wallace and another St. Louis pianist, Sylvester Palmer, with some theorizing that they are, in fact, the same person. Supporting evidence is that Palmer’s recordings likewise use only I and IV chords and he also uses some of the same right-hand figures. Contemporary St. Louis blues player Henry Townsend provides convincing testimony that Wallace and Palmer two were different individuals, in his book A Blues Life (provide link). He knew both men and could cite differences in their playing. Still, it is understandable that such a mistake was made since Palmer’s Broke Man Blues really does sound like it could be Wesley Wallace’s playing, with the music being very much the same as Fanny Lee Blues.

However, Henry Townsend was present in the studio when that track was recorded: “At Sylvester’s session I was sitting right in the studio with him,…and there was no other person involved…no Wesley Wallace.”

All of Wesley Wallace’s recordings, as well as Sylvester Palmer’s, can be found on St. Louis Barrelhouse. However, much cleaner transfers of Wallace’s two solos, Fanny Lee Blues and Number 29, can be found on Down on the Levee.